Welcome to HCI Research for All!

The idea behind the site has always been, and continues to be, the support of HCI researchers in building on, and validating, each other’s work. The aim is to decrease HCI theory fragmentation and so to increase HCI discipline progress, while preserving the on-going technical and human diversification of HCI. The contrast is with HCI community progress, which continues apace.

The site was initially used to develop these ideas on the basis of research, conducted at University College London from 1979 to 2001. The development resulted in the publication of a book, entitled ‘Approaches and Frameworks for HCI Research’, written by John Long and published by Cambridge University Press (CUP – www.cambridge.org/9781108719070). From the date of the book’s publication, that is, 12 February, 2021, it replaces the website, as a citable source for the particular expression of those ideas. The original website has been retained by way of archives of Approaches and Frameworks. The latter may be of interest to researchers in the origin and development of the ideas behind the book.

Feedback on all aspects of the book and the site is welcome and should be sent to myself at <j.long@ucl.ac.uk>. It will be added to the site as a post and the authors informed.

Welcome to ‘A Guide to Framing Design Practice for UX’

The site is used to post the source material for a new book entitled ‘A Guide to Framing Design Practice for UX’ (to be published by Springer Nature).

The new book is in contrast to the present book. The former is about Research, the latter about Practice. Also, respectively about HCI and UX. However, the two books are complementary. The second also cites the first. For this reason, they are referenced here together. Contributors’ biographies are also included.

The posting of the source material in the public domain means that the material can be referenced for comment. However, any such use of the source material must be clearly signalled, for example, by quotes or somesuch.

John Long (April, 2023)

Blyth, Gerred (2023)

Read More.....Usability, UX, Beyond and Back: A Practitioner’s Odyssey

Gerred Blyth, May 2023

For those that entered into the world of Human-Computer Interaction at the turn of the century,the rules of engagement were straightforward: Systems should be engineered to be cognitively

ergonomic. They should be usable. What is usability? That was simple too. It was defined by ISO

9241 as allowing users to achieve their goals with “effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction.”

Each of those three terms had a variety of associated metrics.

Practitioners at this time duly measured those metrics which ensured their systems were

usable. All was well. The ISO standard was well defined, forged in the heat of thorough

committee review. It was clear to all its advocates that it was both necessary and sufficient to

describe a quality user experience.

While ISO 9241 was the “what” of user centred design, ISO13407 offered the “how”. Now in

addition to assessing a system’s usability, there were reliable and repeatable processes to

achieve expected outcomes. Finally, the “what and the how” could all be understood within

broader conceptions of the entire HCI discipline, such at that of Long and Dowell (1989,

reference 0a)

With the zeal of the recently converted, the practitioners in the Class of 2000 explained (to

anyone that they thought needed to hear) that the creation of quality systems really was a simple

affair. It was obvious. Follow the processes, place users at the heart of each step, measure for

effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction, and a good result will follow. And woe betide anyone

that got in the way of this pure and foolproof logic… with distractions of new technologies, or

the realpolitik of limited budgets and time constraints, or – worst of all – patently unverifiable

claims of “but this design is better”.

—

Anyone that recognises the portrait above will then surely recognise at least parts of the

conceptual odyssey that I will now trace out. As a community, as an industry, and as individuals,

in the last twenty years we have journeyed from the primacy of “usability” to User Experience.

The journey has been well documented and has had many heroes. There have been triumphs

and successes. UX has earned its place at the table in powerful organisations. Many of those

same practitioners now believe in the precepts of UX as fervently as they did Usability.

But this journey has also given rise to many challenges and ordeals. A variety of distractions and

inspirations in those two decades have encouraged practitioners to travel yet further, past UX as

it is usually understood, and into new realms that have coloured differently again everything

they were so confident of once before.

Novel project work, different industry verticals, professional development, a spirited mentor or

an inspiring junior team member. Each of these moments has the potential to change how one

sees the world, and how one sees their work as a UX practitioner.

Here I will consider a number of these inspirations – muses, if you will – as a way to define and

challenge ‘what UX is’. As the journey unfolds, we will start to consider UX as a subset in the

wider notion of Quality.

The muses I present here are personal, any journeyman reader will have their own. Each one

has, since the turn of the century, presented the possibility that UX practice is neither necessary

nor sufficient for Quality to exist.

And yet, crucially, the further we travel from UX, from its modes and focus (and those of usability

before it) the more important a homecoming feels.

Muse 1: The Muse of Art and Delight

In 2014 at the UXPA International Conference, I presented my thoughts on my recent

experiences designing with and for artists and performers (Reference 1a). In this domain, the

usual precepts of UX thinking are hard to follow. I described two particular cases:

1. The user is staged as an artistic performer.

In this case, a layman user is engaged with a “walk up and use” interface that has an

artistic intention. Consider the great many interactive installations that are now found at

so many festivals, civic events and corporate head office entrance foyers. (See Reference

1b).

2. An artistic performer is cast as a user.

Examples such as the interactive gloves of musician Imogen Heap (Reference 1c) or the

completely bespoke musical instruments of Kraftwek or Harry Partch (Reference 1d).

Many of these interfaces are designed exclusively for the use of one single performer. The

design and the performance become almost indistinguishable.

In 2014, I continued to argue that the motivations of art and self expression were difficult, if not

impossible, to reconcile with the motivations of user experience, as it is usually understood.

In the first case, the end goal of the interaction is an artistic expression. The creation of

spectacle, or mystery, may be part of that. These multi-sensory immersive experiences are often

geared for gentle sensory outcomes, or surprising moments of delight. All of these outcomes are

not usually thought to be in the dominion of UX.

In the second case, the performer and their sense of performance identity and agency needs to

be in harmony with the creation of a completely novel tool. It is very difficult to imagine this

individualistic quality arising from the typical methods in the UX toolkit.

To be clear, in the last twenty years many UX theorists have included conceptions of delight, or

emotion, or affect, in their models of UX. In fact this was one of the key notions that

distinguished UX from traditional “system usability”. But it is hard to imagine that there is any

practical way to operationalise these ideas so that they will be of utility to artists and

performers working with the kinds of interactive systems described above. Yet, designed and

built they are, and undeniable in terms of quality, in the eyes of the right audience, in the right

context.

Muse 2: The Muse Of Pragmatism and Shipping

UX careers tend to follow one of a number of templates. It may be from “junior” to “senior” or

“individual contributor” to “manager”. Another common path for UX practitioners in the last

twenty years has been to move from UX Research to UX Design and then into Product

Management. This progression is mirrored in many other professions: from understanding, to

creating, to governing. From the many UX practitioners that have followed this path, there is a

common reflection: ‘I only know now how easy it is to criticise something, but how hard it is to

solve it’. (Reference 2a).

UX practitioners are well known to be harsh critics. Indeed, it is part of the core of their role in

many organisations, be it through expert reviews, or design critiques, or primary-research based

UX evaluations. An experienced UX practitioner will deconstruct an experience or an interface

and present winning solutions that will engender greater satisfaction and deeper, more

successful user interactions. That is what they are there to do.

As UXers obtain more experience and become more familiar with the implications of these

winning solutions, for example development costs, or opportunity costs , they will of course

start to see the bigger picture to what was previously “a no brainer for better user experience”.

This is a crucial part of the maturity of a practitioner, and the ability to converse in these terms

separates out the juniors from the seniors and leads in the world of UX.

One of the most impactful ways many UX practitioners will get this perspective is to act in the

role of a product manager. What might be obvious as the best design for user experience in one

aspect of the product suddenly becomes low priority when faced with the harsh reality of what

this work means that users will not get elsewhere. This balancing of UX impact versus effort is

the touchstone of a product manager’s role. Further to that, they must also address the

equally-important ambitions of a never-ending list of other non-UX focused initiatives.

Quality, for a product manager, has UX at its heart but it cannot be in thrall to the concept.

Pragmatic decisions take over, and the primary concern often becomes one of “shipping”. A

system focused on perfect user experience may be something to aspire to, but if it is unreleased

it will never beat the lesser system that nonetheless actually gets into users hands.

The challenge to UX here is to recognise that it is really only one part of the puzzle of the

creation of Quality.

Muses 3 and 4: The Muses of Persuasion and Dark Patterns

Another stepping stone on the path from Usability to UX, and beyond, was the attempt to

harness psychological and cognitive understanding to make products not just emotional, or

affective, but also in some way behaviour changing. The foremost proponent of this concept has

been Professor BJ Fogg at the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab. (Reference 3a).

A variety of interactive design techniques have been researched and documented by Fogg. These

include compelling trigger / notification sound design, to full gamification of apps and other

day-to-day systems.

This concept has been another provocation for those in UX. Is their role to act entirely for the

benefit of their user stakeholders? Should tools empower users or change users? Fogg has taken

great pains to specify the parameters of ethical persuasion. But this stance was not embraced by

Nir Eyal, whose bestselling 2014 book “Hooked: How To Build Habit Forming Products” feels

scarcely palatable after the subsequent decade of mass social media manipulation that has been

so well documented.

Rowing back from unethical behaviour manipulation, and into more familiar “true UX” waters,

we might find ourselves with Dr Harry Brignull and his colleagues who have spent many years

documenting Deceptive Design (aka Dark Patterns, reference 4b). This inversion of the practices

of the behaviour manipulation experts identifies corporates and others who practise these tricks

and publicly names and shames them. The team also works in legal contexts to advise on and

help enforce laws that are intended to prevent manipulative interactive design.

Any UX practitioner being drawn into these themes in the last twenty years must surely also

conclude that a principal part of UX, of the quality of its offer, is its “pro bono publico” nature.

NB: A decade after publishing “Hooked”, and trading on its advice, it would seem that Eyal

reached the same conclusions, by authoring a new volume by the name of “Indistractibe: How To

Control Your Attention”. One might regard this new work as some kind of atonement. Or,

alternatively, an escalation in his own personal arms race with himself.

Muse 5: The Muse of Tech-First Innovation

Among UX practitioners it is an article of faith the user is the centre of the design process. Some

practitioners insist that they are foremost psychologists, and that they can design for any

technology because the human condition does not change. They warn against the very worst

crime of all: that solutions should ever be dictated by technology, rather than by a pure

understanding of user need.

All this is true, to a point. For the Class of 2000, it was easy to confidently smash the looms of the

technophiles and neophytes who bullishly insisted on new features based on barely usable early

technologies. Clunky touchscreen devices, awkward VR headsets, stuttering video meeting

technology, abysmal speech synthesis and recognition, irrelevant QR codes, and a hundred other

“all tech, no use case” ideas were battlegrounds for ‘tech first’ versus ‘user-first’ advocates.

But while these battles were underway, and the UX community were proud of their wins in the

name of their users, others were quietly creating early applications of these technologies,

building early adopter user bases, refining products and, ultimately, contributing to the

development of the actual technologies until every one finally gained adoption, and many

became themselves mainstays of “good user experience”

The challenge posed to UX here is: can it be allowed for designs to be built and promoted that

are clearly too early to be successful, as some kind of selfless act of allowing nascent

technologies to flourish?

Muse 6: The Muse of AI Design

2022 and 2023 have seen an breathtaking acceleration of the public understanding of, and

appetite for, Artificial Intelligence products.

The headline-grabbing AI darling Chat GPT proved to be the fastest growing consumer product

in history, reaching 100 million active monthly users in just two months (Reference 6a.) Dall-e

and Midjourney were following suit with barely believable monthly advances in artistic novel

image generation.

If anyone assumed that the revolution would imperil only the jobs of low skilled workforce they

were quickly disabused of this notion. Creative illustrators and copywriters suddenly found

themselves under existential threat.

Is UX practice next? For sure, in early 2023, with a little guidance the tools can write the copy

and create convincing visual mockups. But that is far from true UX thinking and practice. For AI

to generate successful products and experiences, it would need to be trained on the datasets of

similar successful experiences.

Quickly, the muse of AI Design looks more like a siren. By participating in the undeniably

diverting promise of AI, practitioners are training the very systems that will potentially soon

relieve them of their responsibilities. Like those illustrators and content creators before them,

we see UX designers today sleepwalking into the kind of practice that once had Oppenheimer

reaching for his copy of the Bhagavad-Gita.

In any case, this particular revolution began some time ago with the availability of big data in

online systems.

For many years already, our user experiences have included many dynamically composed lists:

think of a TV set with refreshing lists of popular channels, a website with

algorithmically-generated recommended books or products, a worksystem with dynamically

created ‘next best actions’ and so on. It has been the case for some time that a designer of any

system really cannot know what a particular user is seeing on their screen without having a

profile of that user.

However, this is changing with the advent of generative user experiences. To be clear, these are

not experiences that are created by designers with AI tools, researching with samples of six

participants, or usage data from six million.

These are experiences that are themselves created by generative AI systems (Reference 6b). The

servers will optimise not just individual dynamic components, but entire workflows to achieve

optimal results. The system will measure success of outcomes and modify experiences

accordingly, for every user. The complexity of a user profile, and the amount of flexibility within a

generative interface will be so profound (and, of course, in a machine learning black box) that it

will be impossible for a human practitioner to know or even predict what experience any one

user is having.

And so what role for UX in this new world? What does quality look like when you don’t get to see

it?

We know that AI systems can only generate alternatives if they are given parameters to measure

success against. What are the metrics of success that could be used? A range of output metrics

such as engagement and profit, no doubt. But also we are surely drawn back to three well

researched and well known measures of a system, familiar now for more than twenty years.

Namely: Effectiveness, Efficiency and Satisfaction.

Could it be so simple?

After the Muses, a Homecoming

At the start of this piece I explained that I would outline an odyssey that would be familiar to

many UX practitioners in the last twenty years. The muses I have identified are definitely

personal, but also shared by many individuals, and by the UX community itself.

And so what becomes of a practitioner undertaking this journey? What impact of the muses?

Each one alone is enough to inspire a completely different destination. Those paths are

engaging, intellectually satisfying, and likely well remunerated.

For many UX practitioners, the position is one that is adopted intimately, and will perhaps

forever colour their perceptions. Even as we dalliance with alternative paths and muses such as

the ones described here, UX is never far from mind, and it influences even the most unlikely of

projects and topics. Like Karl Popper’s Scientific Method, UX practice is ‘a way of operating’ that

will likely never depart, and will always be of use.

To stand at one remove from our own experiences, we might also think about the qualities of a

new practitioner that we would want to join our team if we were trying to create a quality user

experience for an as-yet-unknown context. Would it be advisable to choose the person dipping

their toes into art and performance? Or a product manager in the making? A behaviour change

advocate or protector? A tech enthusiast? An AI entrepreneur? No, we would be advised to

choose someone with very traditional UX skills. Someone that can understand real user needs

and engineer solutions to truly satisfy them.

But then: If a pure UX mindset is of such great value, to what end are these muses of any benefit

to anyone? If a homecoming is proper and desirable, what is the point of it all? Well, we might

think of these professional and intellectual muses as grist to the mill. While each one would be a

legitimate pursuit on its own terms, perhaps their true value lies in the journey itself, the lessons

therein, and their compound interaction with each other and with the original core set of HCI

and UX values. Learnings from one amplifies the skills learned in the other. They afford

unexpected evolution to us – as practitioners, yes – but also as agents in the world. As people.

And what was supposedly “work” all along was in fact growth. Here, in the final analysis, I am

reminded of Pirsig writing in 1974: “The real cycle you’re working on is a cycle called yourself”

References:

0a: https://hciengineering.net/long-and-dowell-1989/

1a:https://www.slideshare.net/UXPA/how-can-we-apply-the-motivations-of-art-selfexpression-and-playfulness-to-ux-and-vice-vers

a-gerred-blyth

1b: https://amt-lab.org/blog/2021/10/artistic-futures-digital-interactive-installations

1c: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ci-yB6EgVW4

1d: https://www.bbc.co.uk/music/articles/b49cbf91-9172-4881-9501-7fb5f87700a5

2a: https://rosenfeldmedia.com/books/product-management-for-ux-people/

3a: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Persuasive-Technology-Computers-Interactive-Technologies/dp/1558606432

4a:https://www.amazon.co.uk/Hooked-How-Build-Habit-Forming-Products/dp/B00HZOBOUO/ref=sr_1_2?crid=38N20V2EPQJ66&

keywords=nir+eyal

4b: https://www.deceptive.design/

6a: https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growing-user-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01/

6b: https://prototypr.io/post/generative-ai-design

Chakraborty, Seb (2023)

Read More.....Topic of UX

The topic of UX is complex and struggles with definition, scope, and perceived utility. At the same time, everyone wants it, feels it’s important and yet no-one completely owns it. Experience isunique; mine is mine and yours is yours and yet design would get quite complicated withoutsome commonality, a set of norms, rules of thumb or good old-fashioned principles.

UX Approaches

The UX approaches, of the late 90s, early 2000s, was largely based on a linear developmentcycle. where ideas are conceived, requirements are gathered, designs are built, tests areconducted and eventually the e.g., the thing is launched and needs to be operated and maintained.

Growth in Technology

Since the start of the 2000s, consider how the growth in technology has become exponential and reshaped every aspect of our lives. From mobility to metaverse, IOT to Augmented Reality, the world of experience has become rather too complicated and while UX has becomeessential, it inhabits as uncomfortable space, where it’s tricky to define and problematic to own.The UX designer’s role (assuming there is such a role in a company) their work is often confined todesigning a few widgets for the webpage.

Framework and Frames

Frameworks and frames, act as points of reference and an opportunity to simplify. They alsoperhaps help put in context the things that need to be thought about. Given that most things thatget built are produced by companies, one useful way to re-frame is the Product Centric framing, which positions three intersecting circles, describing the cross-cutting concerns of business, technology and UX.

Illustration

Consider the choice of a microprocessor, sitting in the intersection. The technology consideration is relatively clear, encompassing requirements to do with chip fabrication,semi-conductor quality and number of transistors. The business consideration will be largely to do with the bill of materials. Choices may be impacted by inflationary pressures, impacts onsupply chain and any other political dimension, for instance, China’s blockade of ships to Taiwan. The UX, angle will be that the chip will need to both be compatible with the operating systems, theapplications and that they perform at the right speed to deliver the right experience.

At this level of framing, it’s straightforward to appreciate that functional and non-functionalrequirements that need to be satisfied in the building of a ‘thing’. The trillions of things in existence today, whether they be physical hardware devices, component parts of devices, websites, smartphone screens, in car displays, 3D headsets, the UX challenge becomes staggeringly complex.

Key Ideas

- UX is dead, long live UX

- How does a product centric frame for UX help?

- How do you do UX at speed in the era of exponential?

Cummaford, Steve (2021)

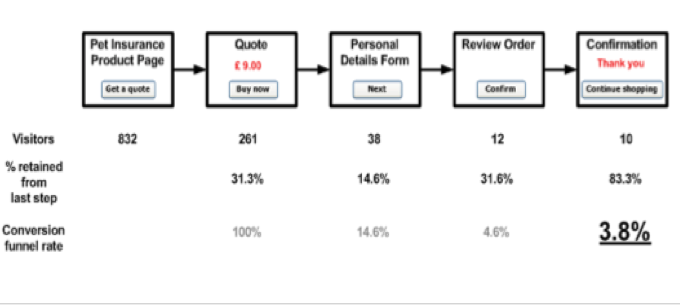

Read More.....Business-to-Consumer Best-Practice Update

Revenue for digital media and technology in general, and e-commerce in particular, has grown. Turnover for e-commerce has increased from about £20 billion in 1998 to about £2 trillion per annum globally. Hardly surprising then, that commercial best-practice has attracted resources, resulting in its development and advancement. Future research needs to take account both of how to apply current best-practice in the acquisition of HCI-EDPs and what format best suits their application to current best-practice design. To the latter ends, the changes to best-practice, since the completion of the research, are identified and implications for best-practice and for HCI-EDP application format noted. Future research would do well to take account of both sets of implications. Such changes in best practice follow:

1. From design for usability to design for user experience (UX).

2. From design methods to design methods, enhanced by technical advances in data capture, as exemplified by UX analytic tools, such as Adobe Analytics and Content Square.

3. From simple online transaction testing to online ‘design funnel’ testing.

4. From simple online transaction testing to online ‘AB’ testing.

5. From structured analysis and design methods to ‘lean UX’ design methods.

6. From the design problem to the minimum ‘viable product’ (MVP).

7. From process design methods to ‘atomic’ design methods.

8. From individual online user testing to online ‘scaled up’ user testing.

Note that in all cases, the full range needs to be included.

All these best-practice changes can be recruited to the design practice, used in the case study, to support the acquisition and validation of HCI-EDPs. Such application, however, would necessarily require the mapping of the novel change concepts, such as ‘lean’ and ‘minimum viable product’ to those of the conception, such as ‘design problem’ and ‘design solution’ and, indeed, ‘HCI-EDP’. The format of the latter for best practice application was an issue at the time of the research and remains an issue now.

In conclusion, as concerns e-commerce systems, it is clear, that they were a promising area of research, in terms of their potential for commercial development. The selection of physical goods e-commerce transaction systems has also proven to be an area of commercial interest and success. There is no shortage of such systems, with Amazon emerging as perhaps the best known, and possibly biggest. Information e-commerce systems, however, have almost disappeared in the form characterised in Cycle 2 development. The general class-level description of transaction systems for information may still be valid, for example, the sale of virtual goods in games or the metaverse, but SMS news alert services as such hardly exist. However, the particular example is less important than the development of the HCI-EDP conception and the class-based approach themselves.

Grant, Courtney (2023)

Read More.....Education

I completed my MSc in Human-Computer Interaction with Ergonomics. The course provided the foundation for a career in user-centred design.

Employment

After completing my MSc, I joined an engineering consultancy as a Human Factors consultant. I began working in multi-disciplinary design teams. I worked in defence, nuclear, and rail. I worked on both physical and software Ergonomics projects.

I also worked on safety assurance projects, which benefited me. I gained much from the rigorous approach that I needed to apply on these safety projects. This influenced the way I frame my Human Factors work.

Practice

I would describe my practice as varied. I have worked on projects that focus purely on physical Ergonomics. I have worked on projects that focus purely on software Ergonomics. I have worked on projects that integrate the two. For example, I have worked on projects where the organisation procured software systems from different suppliers, all of which we need to physically integrate onto the desks in a control room. I have also looked at the user experience of wider systems, paperwork, procedures, and so forth.

My practice is highly evidence-based. I base my recommendations on the best evidence, drawing on the literature from Ergonomics, Human Factors, HCI, and so forth. If I make a recommendation, I map it back to the relevant literature, or to the relevant standard clause. I read extensively. I trawl through the literature in this space. I collate what I find into an Excel-based commonplace book. I capture key insights from research, standards, guidance, and so forth. Before I kept a commonplace book, I used to lose track of key sources that I would come across. If I then encountered a similar problem where this source would also prove useful, I would have to search for it again from scratch. Keeping a commonplace book helps me to work more efficiently.

Analysis

When it comes to analysis, I like to be creative. For example, I create my own spreadsheets to find different patterns in the data I collect about systems. I also like to combine analytical methods to create something more robust. This helps me to understand a given situation from more angles. I have done this when I have looked at the risk of use error with user interfaces.

Evaluation

When it comes to evaluation, I like to stick to tried-and-tested methods. For example, when it comes to collecting quantifiable subjective user data, I prefer to stick to the likes of the System Usability Scale and the Single Ease Question. They are well-validated questionnaires, underpinned by research. If there is however a gap between what we need on a project and what is currently out there, then I would look to develop my own questionnaire.

Design Practice

In my experience, the degree to which you engage in these design practices depends on the project. It usually is a mixture, but the mixture of each form of design practice will vary by project. For example, on projects with greater amounts of uncertainty, I will need to use more trial and error to work through the assumptions.

Design Problem

As an example of a design problem that I have encountered, I have worked on projects where the project has procured software, but we cannot change certain elements of the software because it is core to the product. These elements may not be ideal or the “gold standard” from a Human Factors perspective. However, we must nonetheless find a way to make it work.

As another example of a design problem that I have encountered, I have worked on projects which involve bringing multiple software user interfaces into use, which a given operator needs to use. Therefore, to minimize the risk of negative transfer, these software user interfaces need to be compatible with each other when it comes to the user experience.

Systems Perspective

It is important to take a systems perspective. It is important to look at the whole environment where a given device needs to operate. For example, when it comes to control room design, you must think about how each control room element will integrate into the control room, from software to hardware to all other elements. Your thinking must extend beyond any one aspect.

Approach

I use the steps from BS EN ISO 9241-210 as a broad framework for my practice, most notably to understand the context of use, specify the user requirements, produce design solutions, and evaluate the design until we reach a fit-for-purpose solution. For each these steps, I use specific approaches that work for me.

When it comes to understanding the context of use, one approach I like to use is Cognitive Work Analysis, and in particular the contextual activity template. I use this to map out all the system’s functions and the different situations that the end-users will encounter. I also use Tabular Task Analysis. I map the user’s tasks out in the subject-verb-object format. I first started using this format after seeing the sentence structure outlined in the book “Guidelines for Developing Instructions” by Kay Inaba et. al (2004). I found this useful as an approach to task analysis. I created a template in Excel that divides up these elements of a user’s tasks in this way. This approach allows me to develop task analysis in a consistent, systematic manner. At this stage, I also like to record an inventory of all the system’s elements. For user interfaces, this would mean recording each user interface screen, and each user interface element. My approach is to collect vast amounts of data, and then narrow the focus down as needed.

User Requirements

When it comes to understanding the user requirements, I apply the relevant Human Factors parameters to the context of use. I compile spreadsheets that contain principles, patterns, guidelines and so forth. I record the source, a link to the source where applicable, and the key insights from the source. I also include keywords to search for. This allows me to filter and search for patterns across what I have collected. It is a commonplace book. I trawl through sources of evidence for anything that could be of help to me. I arm myself with hundreds of principles, patterns, and guidelines. It is then a case of applying the right parameters to the situation.

When it comes to producing design solutions, I like to work up a range of options for solutions, and this is where I will prototype different solutions. For example, I have used PowerPoint to quickly put together interactive user interface prototypes. I like how IDEO’s CEO Tim Brown talks about the need to “build to think.” I like IDEO’s “fail faster to succeed sooner” approach.

Evaluating Design Solutions

When it comes to evaluating design solutions, I assess each proposed design solution against the parameters that I have identified previously. For example, this could involve assessment against clauses from standards, such as consistency of the positioning of controls. This could also involve performance-related parameters, such as task completion rates. This could also involve collecting subjective feedback from users, such as via the Single Ease Question and the System Usability Scale, to capture quantifiable feedback. In addition to this, this could also involve collecting qualitative feedback from users.

Framework

I like to employ the framework outlined in BS EN ISO 9241-210. Specifying the context of use, understanding the user requirements, creating design solutions, and then evaluating these design solutions until you arrive at a suitable solution provides a robust framework for design practice.

Case Studies

I participated in the 2019 BTNG hackathon at the Microsoft Reactor office in London. Microsoft Reactor streamed the event live on their YouTube channel. The hackathon sought to reduce the impact of “brain-drain” in Nigeria, where highly skilled Nigerian professionals leave the country to work in other parts of the world. At this event, I worked in a team with two UX professionals, a Software Engineer, and a medical student. We developed a prototype software app that aimed to improve access to healthcare in parts of Nigeria by connecting them remotely to Nigerian Healthcare professionals working in the diaspora.

We researched the current healthcare situation in Nigeria. We identified huge challenges, both in urban and rural areas. Initially, we wanted to focus our solution on helping people in rural parts of Nigeria. However, issues with literacy, internet access and electricity meant that this would not currently be practicable. Therefore, we decided to focus on urban areas.

We prototyped our solution in Sketch, and the Software Engineer created the app itself in Android. The registration page allows users to add key information to their profile, such as details about their previous medical history. The app allows to confirm whether there is a medical emergency, and in this case, the app connects the user to the relevant emergency health services. For all other matters, the app offers three options to the user. The first option allows the user to look through a directory of common illnesses. The second option allows the user to find nearby health facilities. The third option allows the user to directly connect a healthcare professional (either by phone or via a video call).

This experience provided insights into the infrastructure challenges associated with delivering solutions into this problem space.

Example of Framing Design Practice

I worked on a major control room upgrade project. The project procured new control and communications systems for the operators to use. Different suppliers developed these different systems. This risked introducing inconsistency across these systems.

I took action to promote consistency across these systems. I created a style guide, which mapped out all the key features across all systems and specified the style and format for the suppliers to implement to promote consistency across the systems.

I took a pragmatic approach. I assessed the most developed system against the relevant Human Factors parameters. I then used the features from that system to define the style for the less developed systems to follow. Once the suppliers developed each of the systems, the style guide formed the basis for the integration assessment of all the systems.

My control panel design work is another example of how I frame my design practice. To specify the control panels on a particular project, we worked with end-user representatives to look at the tasks that they need to do with the control panels. We used that information to determine what control and indications they needed the control panel to include. I then developed an interactive PowerPoint prototype of the proposed solution to make sure it met the needs of the users. We then implemented the control panels, developed training guides, and trained users on how to operate them.

Ways Ahead for Framing Design Practice

I can see more conduct and reporting around equality, diversity, and inclusion. We need to use fit-for-purpose methods for this emerging area to enhance the way professionals deliver solutions. For example, in 1993, Jakob Nielsen said that the thinking aloud method is the most important usability method. This will be the case for users who are functionally able to articulate their thinking verbally. However, specific users may struggle with this method, such as people with dementia or aphasia. I expect to see professionals develop more inclusive approaches to design practice, such as further development of multi-modal communication approaches to user testing.

I also expect to see more conduct and reporting around sustainable design, with professional helping to develop better smart technology that will support optimal use of energy.

Additional Points

I also like to build in approaches from other fields. For example, I like Triz (Theory of Inventive Problem Solving), and specifically, the approach set out by Gordon Cameron in his book “Trizics.” It helps me to think about a problem from different angles. For example, there is a tool known as “Nine Windows.” This encourages you to look at a problem at the supersystem, system, and subsystem level. In addition to that, it encourages you to look at a problem in terms of its past, present, and future. This approach is incredibly useful for Human Factors work. It helps me to think more broadly.

References

Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. Harper Business.

Cameron, G. (2010). Trizics: Teach Yourself Triz, How to Invent, Innovate and Solve Impossible Technical Problems Systematically. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

IDEO (2013). Why You Should Talk Less and Do More. Available at: https://designthinking.ideo.com/blog/why-you-should-talk-less-and-do-more#:~:text=When%20you%27re%20trying%20new,re%20doing%20is%20an%20experiment.

Inaba, K., Parsons, S.O., and Smillie, R.J. (2004). Guidelines for Developing Instructions. CRC Press.

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability Engineering. Academic Press Inc.

Middlemass, James (2023)

Read More.....Notes from the Coal Face

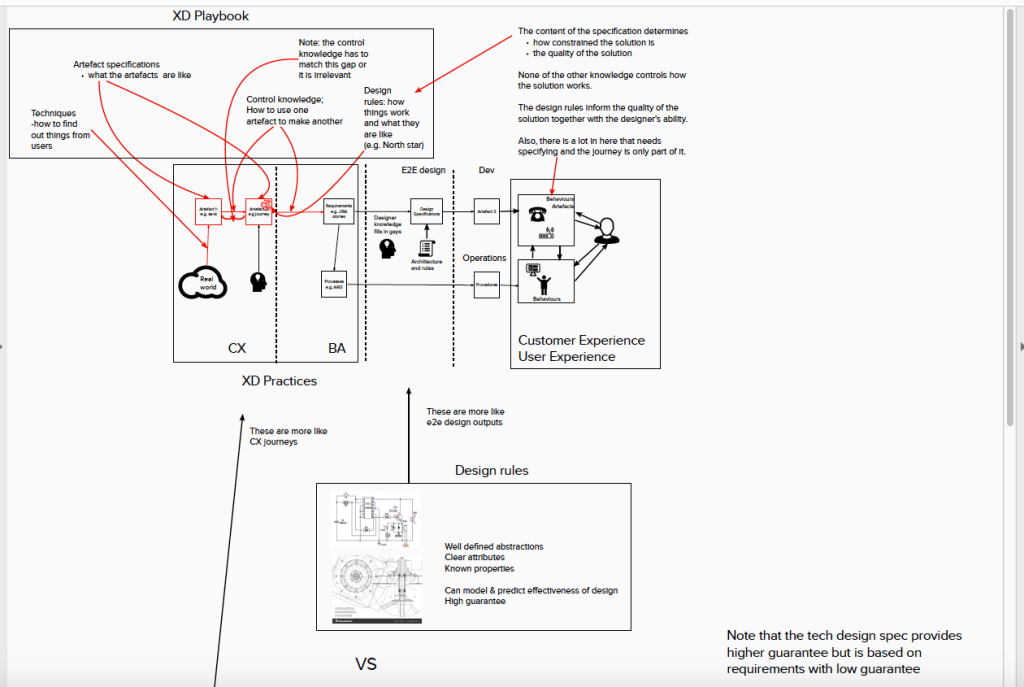

Experience Design (XD)

Some notes from the coalface: For the last few years I’ve been back in the ‘experience’ fold and am in a team currently known as ‘XD’ for Experience Design (‘currently’ because we spend more time in reorgs than in a stable structure! Rearranging reporting lines is guaranteed to solve all possible problems.). Anyway, Experience Design is supposed to indicate a combination of ‘Customer Experience’ and ‘Colleague Experience’ but in practice it’s much more of the latter and less of the former. In reality, most of the team are business process designers and much of the work is done using a tool called ‘ARIS’ which uses a fairly widely used notation called BPMN (business process modelling notation). Unfortunately it’s such a cumbersome tool that a lot of design decisions are made to suit whatever is expedient given the limitations of the tool and the notation! Interestingly, UX is treated as a separate ‘add on’ to CX. We’ve also got an interesting practice whereby the whole customer experience is reinvented for each product that launches, but as its so difficult to change anything it turns out to be pretty much the same each time, or to have minor variations for each product that just create confusion. Consequently, most of the team is kept so busy continually reinventing the wheel there is hardly any time left to improve anything.

Happy Path Processes

I’m fortunate to be working on a more ‘green field’ project where we have a bit more latitude, but at this stage of the game that largely involves designing very simple ‘happy path’ processes then tracing individual data items through them to make sure users are going to be presented with the right bits to do their job – not as straightforward as you might imagine, because adding an attribute into a system interface is a bit of an undertaking. Even identifying which attribute is required can involve significant work – we recently required one called ‘port speed’ and were excited to discover the product (data) model contained several similarly named attributes with no indication of which was which.

Benefits

That said, the benefit of being on this project is that we’re less constrained in how we’re working and free to model things in whatever way fits what the system designers want to know. The wider team, especially managers, have the notion that they should be establishing ‘best practice’, which generally involves attempting to use whatever document has been well received on a single project (usually only because someone put a lot of work into it) as a template and then wondering why the next project struggles to use it on a slightly different problem. I’ve reminded them of the maxim that ‘if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail’, but it doesn’t seem to sink in. It also doesn’t appear that there has ever been any work done to find out what the recipients of our designs need – they usually just wait for us to produce the first draft and then ask us to add whatever they think is missing and claim that it has always done that way, was due months ago and has been holding them up!

PS

By the way – if you thought there was some disappointing literature associated with UX, have a look at CX! It’s something else.

Sinclair, James (2023)

Read More.....PROJECT – ACCESSORIES COMPETITORS’ REVIEW

Method

We evaluated the accessories-buying process for three different companies: Samsung, Apple, and Google. To perform a competitive analysis, we judged each site against the same set of heuristics, defined below. Components and pages were judged on a three point scale: 1=poor, 2=OK, 3=good.

Competitors

We looked specifically at three flagship phones: the Samsung S10, the Apple iPhone X, and the Google Pixel 3. All are high-end, expensive, models and are likely to appeal to a similar demographic. The websites for each product have many similarities, but have their own style.

Journeys

For each retailer, there are two main purchase routes for accessories.

Marketing

Accessories are marketed on PCD pages and on theiown PDPs. The user is likely to enter this journey when she is looking directly for accessories and browsing relevant pages.

Upsell

Certain accessories are also suggested when the user makes a related purchase. We compared the buying journey for the Samsung S10, the Apple iPhone X, and the Google Pixel, and evaluated how accessories were upsold for each.

Heuristics

Efficiency – Users should be able to move through the process in the manner most convenient to them. If possible, there should be shortcuts for some frequent actions.

Consistency – The site should have the same characteristics and behave in the same way across different pages.

Effort – The user should not have to remember details from previous pages. The user should not feel trapped. The user should not wonder what they are meant to do.

Flexibility – Users may behave differently than expected. The site should allow users to modify their actions and navigate in their own way.

Generalisation – Users prefer sites to work the same way as all the other sites they already know.

Clarity – The user should always know where they are and what they are looking at. Familiar words, phrases and concepts should be used. Buzzwords and technical language should be avoided.

Feedback The system should let users know when an action has been performed.

When evaluating each page, we highlighted particular issues and scored them 1–3, where 1=poor, 2=OK, 3=good. The ‘heat maps’ represent overall scores for the entire journey. However, while a user journey might score low on clarity, for example, there might also be elements within that journey that score a 3, if the copy has been particularly clear for that specific

component. These findings have been drawn out on the detailed pages that follow.

Accessories

Executive Summary

In a nutshell, Samsung scores relatively poorly on the marketing journey. Whilst the Accessories PCD is extremely clear, and scores highest out of the competitors, the Product Finder is awkward to use. This is because of issues with the filter, sort and default listing. It therefore scores low on effort, generalisation and clarity.

On the other hand, Samsung scores highest on the Upsell journey. Samsung scores 2: OK, on everything but flexibility.

In general there are missed opportunities to upsell more products, but the overall journey is straightforward. Improvements can still be made at a more granular level.

Marketing Journey

Summary

Samsung scores relatively poorly on the marketing journey. Whilst the Accessories PCD is extremely clear, and scores highest out of the competitors, the Product Finder is awkward to use. This is because of issues with the filter, sort and default listing. Additionally there are major problems with the S10 journey as it is impossible to find PDPs for these products, as “Learn More” links back to the Accessories tab. It therefore scores low on effort, generalisation and clarity.

Apple is surprisingly inconsistent. They lose marks for clarity because they do not highlight the compatibility of their products.

Google scores highly, but it should be noted that the site is a much smaller shop. Fewer products, fewer journeys, and fewer options, generally means a simpler, easier-to-use site.

Samsung S10 Apple Iphone X Google Pixel

Table 7.1 Marketing Journey Scores

Consistency 1 1 3

Effort 1 2 3

Flexibility 1 2 3

Clarity 1 1 2

Feedback 3 2 3

Efficiency 1 1 3

Generalisation 1 2 3

1…..Poor 2. OK 3. Good

Samsung

Mobile Landing Page

Finding

The mobile landing page serves as an excellent introduction to the Galaxy series. However, the way the actual products are linked to is unusual when compared to Apple and Google, as we’ll see on the next pages. Regarding the accessories journey, it is quite easy to find the flagship phones, but quite awkward to find the accessories.

Effort 2 Clarity 2

Finding

The product line is contained with a strip that behaves like a navigation bar, but doesn’t look like one. The images are large, but the text is unusually small. Users would also expect something like this to be located at the top of the page, not third down.

Clarity 1 Generalisation 1

Recommendation

Consider moving to the top of the page, shrinking images, and enlarging text.

Finding

The images are not clickable. The links also open in new tabs, which is unexpected.

Efficiency 1 Generalisation 1

Recommendation

The images should be clickable. The links should open in the same tab.

APPLE

iPhone Landing Page

Finding

The nav bar is present throughout the site, allowing quick navigation.

Effort 3 Consistency 3

Finding

Accessories are given own category in navigation bar. This is expected, but the use of icon plus text improves visual clarity and makes the page very scannable.

Generalisation 2 Effort 3 Clarity 2

Finding

There is also an Accessories section further down the page.

Effort 2 Flexibility 2

Phones Landing Page

Finding

A nav bar is available on both this page and the Accessories PCD.

Consistency 2 Generalisation 2

Finding

Navigation bar offers clear categories illustrated with image and text.

Generalisation 2 Effort 3 Clarity 2

SAMSUNG

Accessories PCD

Finding

The mobile accessories page is clear and easy to use. The most popular categories are easily accessible and there are multiple links through to relevant pages.

Effort 3 Clarity 2

Finding

The first heading reads like a sub-heading. Title is currently conversational, and the subheading is descriptive. Clarity would be improved if these were swapped around.

Clarity 2

Recommendation

“Mobile Accessories” should be swapped with “Get More from Your Device”.

APPLE iPHONE

Accessories PCD

Finding

Quite difficult to get to “all”.

Effort 1 Generalisation 1

Finding

Colours not clickable.

Feedback 1

Finding

“Shop by category” probably the most useful thing on this page, but buried at the bottom of it.

Efficiency 1

Finding

Apple provide a PCD specifically for iPhone accessories. For Samsung this is only available for the mobile category. Like Samsung, the Apple PCD provides a link to the Accessories finder in the Key Visual.

The page then features a number of convenience categories: Featured, Air Pods, What’s New and Shop by Category.

Flexibility 3 Clarity 3

GOOGLE PIXEL

Accessories PCD

Finding

Follows a similar pattern to other retailers with featured products taking up most space, but there are also clear links through to “All Accessories”.

Generalisation 3 Clarity 3

Finding

Generally clear copy, which is easy to read and informative.

Clarity 3 Effort 2

SAMSUNG

Checkout

Finding

Unexpected behaviour. The “Back to Shop” does not take the user back to results, but to a different section of samsung.com

Generalisation 1

Recommendation

Back button should go back.

Finding

Too many elements. The page design is distracting.

Clarity 1

Recommendation

Checkout could be simplified, allowing the user to focus on completing the purchase.

Finding

“Customer also bought” shows unlikely or redundant items.

Clarity 1

Recommendation

Change to “You might also like” or similar phrasing.

APPLE iPHONE

Checkout

Finding

A featured product is recommended, which allows Apple to upsell something not directly connected.

Clarity 1

Finding

Few additional products are made available at this point.

Flexibility 1

GOOGLE PIXEL

Checkout

Finding

Simple checkout design allows user to focus on completing their purchase. Again, this comes at the expense of flexibility, but it is still easy to find your way back.

Efficiency 3 Effort 3 Flexibility 1

Upsell Journey

The upsell journey evaluates how accessories are sold to the user once they choose to buy a flagship phone.

The scoring is the opposite of the marketing journey. The Samsung S10 scores highest, Apple iPhone second, and Google Pixel third.

Samsung scores 2: good, on everything but flexibility. In general, there are missed opportunities to upsell more products, and there are times when the user’s control is limited. There are various issues on each individual page, but the overall journey is straightforward.

Apple achieves similar scores to Samsung and has many of the same issues. Some parts of their site behave inconsistently or have unexpected behaviour so they lose points for consistency and generalisation.

Google scores lowest because they have a highly inflexible model. Once the user decides to purchase a Pixel phone, they are funnelled through a series of pages and given little opportunity to purchase accessories or go back. The buy process is very straightforward, clearly signposted, and easy to use, but actively prevents the user from modifying options or leaving the train- tracked buy journey.

Table 7.2 Upsell Journey Scores

Samsung S10 Apple Iphone X Google Pixel

Consistency 2 1 2

Effort 2 2 2

Flexibility 1 3 1

Clarity 2 2 2

Feedback 2 1 1

Efficiency 2 2 2

Generalisation 2 1 2

1…..Poor 2. OK 3. Good

Samsung S10

Finding

Accessories section is not clearly marked, nor described.

Clarity 1 Generalisation 2

Recommendation

Use a clear in-line header.

Finding

Images, copy, and structure combine to create something flashy, but they should instead combine to create something clear. User should be able to answer “Where am I now? What am I being shown?”

Clarity 1

Recommendation

Emphasise Accessories.

APPLE

SLP

Finding

Accessories section at very bottom of PDP, and not accessible from a nav bar.

Generalisation 1 Effort 1 Consistency 1

Finding

Accessories clearly marked with simple copy and linked through to accessories PCD.

Clarity 1

Google Pixel

SLP

Finding

Impossible to get to all accessories. There is no link to accessories on the page. Must go through “Shop My

Case” and then reset filters.

Efficiency 1 Flexibility 1

Samsung S10

Accessories Tab

Finding

Relationship between information and images too loose. The large amount of white space makes some items invisible on smaller screens.

Effort 1

Recommendation

Condense white space.

Finding

Descriptive info is good. Page structure is clear. However, the fade-in animations, combined with the very large amount of white space, make the page quite hard to scan.

Clarity 2 Efficiency 1

Recommendation

Condense white space, reduce animations.

Finding

No option to Learn More, only Buy Now. This is particularly frustrating if user has reached this page from the PF and is now stuck in a loop.

Effort 1 Generalisation 1 Consistency 1

Recommendation

Create links to PDP.

APPLE iPHONE

Buy Page

Finding

“What’s in the Box” has to be expanded, but contains clear, useful information.

Clarity 2 Effort 2

Finding

No mention of accessories at this point in the buy journey.

Generalisation 1

GOOGLE PIXEL

Buy Page

Finding

Once the buy button is clicked, the purchase journey is kept on strict tracks. It is a simple experience, but there is limited opportunity to add accessories, or to go back for more information.

Clarity 2 Flexibility 1

SAMSUNG 10

Checkout

Finding

User not given a final summary of what’s included.

Clarity 1

Recommendation

Show users what’s already included so that they can

make educated choices about what to add.

APPLE iPHONE

Checkout

Finding

Checkout for iPhone upsell journey is identical to the checkout for marketing journey. Recommendations are not tailored to choice.

Finding

A featured product is recommended, which allows Apple to upsell something not directly connected.

Clarity 1

Finding

Few additional products are made available at this point.

Flexibility 1

GOOGLE PIXEL

Checkout

Finding

The Accessories buttons now says “Buy”, where previously it said “Add to Basket”. On some pages of the .com, there is no CTA at all, and the user must click the card. This is inconsistent.

Flexibility 1 Consistency 1

Finding

There is no link to additional accessories.

Flexibility 1

PROJECT – DA BRILLIANT BASICS

Introduction

In 2019 Sinclair was asked to improve the user experience for domestic appliances. This entailed reconciling two sitemaps, one from the product team and one from SEO specialists. Creating new pages to house search engine content and refining existing page types to improve engagement and the user journey. Finally taking a product finder from one national site and refactoring it to another.

The work delivered the following assets, a new sitemap, an AEM prototype and a Virtual Assistant, to be tested with users in laboratory-based sessions.

Methodology

15 participants were recruited for a lab-based usability study. Sessions were organised into three sets, so providing time for findings from one set to be fed into the design and tested in the next set.

Sample and Equipment

Sample

Fifteen participants were recruited from the target audience, for face-to-face Lab-based sessions .

All participants had purchased a domestic appliance within the last three years. They were drawn from ABC1 and were split between male and female, urban and rural, ages 20–65, and approximately half owned a Xxxxxx product.

Lab Equipment

Desktop Windows Mid range tower + screen Desktop Mac 21.5-inch iMac

Tablet Android

Tablet iOS

Phone Android

Phone iOS

Sound Recorder: Tascam DR-40 – 4-Track handheld digital audio recorder

Software

OBS device recording software

Sessions

Each session had a facilitator and a note taker.

The facilitator introduced the study and asked the participant for their consent to record the session. The participant was then handed a form and asked to read and sign if they agreed to how the recordings and data would be used.

The sessions ran for 1 hour and were split into three parts; an open-ended interview, prototype testing and a tree test.

The interview was open-ended and took approximately 15 minutes and explored the customer journey for purchasing a domestic appliance. The interview was recorded on an audio device.

Prototype testing ran 25–30 minutes. The scenario discovered during the interview was used to test the prototypes. The participant was allowed to proceed without interruption, and then asked to retrace their steps, and questioned about their behaviour and choices.

Where time permitted, participants were given additional scenarios to test different aspects of the prototype. Areas and content that had not been covered through the participant’s free exploration were prompted or walked through.

All video and recordings were stopped for the Tree test. The test was run on a desktop computer and self- administered and the data capture was automated. Each participant was given an overview of the test and guidance on how to use it. The order of the tasks was randomised.

The tree test was given to further participants as a web link, from both within Cheil and externally in order to drive up the response numbers.

Analysis

The qualitative data were printed and were reviewed to identify repeated ideas, issues, or findings. These were then tagged with codes or themes.

The tagged data were then grouped into categories, which form the backbone of this report.

AEM Prototype

The primary functions of the AEM prototype were to accommodate the new sitemap, improve users’ engagement with content and facilitate the user’s journey through the category hierarchy.

To achieve this pages were created directly in AEM. The benefits of this approach were threefold. Firstly, as all pages have to be constructed out of the components available, it ensured that this condition was met. Secondly, it allowed construction of a hi-fidelity prototype that would function, for the most part, identically to published pages. Finally, it allowed exploration of what type and combination of components would deliver the best experience.

Summary Findings

Product Category Detail (PCD)

A number of participants would not scroll down the page. The first barrier was the size of the key visual. Taking up the entire view port, it gave a false impression that no further content was available and/or prevented participants from initially seeing more content.

Images were hugely important to grab participants’ attention and identify the content. The lack of suitable images in V1 created a barrier to engagement.

All search category items were linked to the relevant new SLPs. However, participants expected a different behaviour depending on content type. Category ranges, Family Hub, American Style, should go to the SLP, whereas SEO descriptions such as colour and size should go to a pre-filtered product finder page (PFP).

Search Landing Page (SLP)

Most participants did not interact with feature benefits when they were presented in a carousel. The carousel was generally missed. This was especially the case on the Xxxxxxx mobile, where the navigational arrows were off the front screen. Where the participants saw the carousel animate, their attention was drawn to it.

The ‘Buy now’ call to action (CTA) was off-putting to a number of participants, as they were in a research mode and not ready to purchase.

Headings and images were scanned, but sub-headings and descriptions were missed or ignored.

Unsurprisingly, participants engaged only with copy that addressed topics that they were interested in.

Participants were put off or puzzled by technical jargon and brand terms. Replacing .com’s content with tangible product copy from AO.com worked better.

Product Detail Page (PDP)

At this stage of the user journey, features and benefits were not very useful. Participants relayed that they had already seen this type of content.

Participants responded well to ‘How it stacks up’. They were able to identify that the middle card was the one described on the page. Furthermore, participants attempted to compare items. The usefulness of this was questionable due to the wording and presentation.

Most participants tended to focus on the product specification. Here, time and attention were given as they tried to find answers to the questions they had about size, energy efficiency, fridge to freezer ratio and so on.

Reviews were of interest, but taken with a pinch of salt as they were on the manufacturer’s website.

Navigation

Creating a series of pages the user could identify and navigate was a challenge. When testing a user’s flow through the three main pages, the results were mixed.

Changes made during testing improved the forward flow, allowing participants to navigate to deeper content.

When participants were asked to navigate back or between sections, the pages generally failed to support this task. Typically, participants did not look within and/ or identify the navigational components, instead preferring to use the browser’s back buttons or the site menu. These results are acceptable, but disappointing as the minimum requirement is to ensure that users are aware of the options available to them

Product Category Detail (PCD) V1

Issue: participants did not scroll. The key visual image was too large, which enticed users to click through to ‘See all fridges’ rather than to explore the page.

Recommendation: reduce the height of the key visual in order to pull additional page content into the view port.

Issue: the anchor menu, under the key visual was mostly ignored. Additionally, participants that were questioned did not clearly understand its purpose, thinking that it would link to new pages.

Recommendation: move above the key visual and consider a more descriptive label, ‘see what’s in the page’.

Issue: ‘Choose by feature’ left participants slightly confused as size, colour, and ice maker do not form a coherent group.

Recommendation: split these into categories, size, colour and features.

Issue: some participants did not engage with the page content due to the style and quality of images.

Recommendation: participants typically expressed a preference for photos rather than icons, and liked images of products in context.

Issue: the order of content and topics chosen did not map onto the way participants were attempting to search for content.

Recommendation: reorder the page and use terms and descriptions that address participants’ concerns.

Issue: some participants tried repeatedly to click on the image to progress their journey, not realising that this could only be done through the CTA.

Recommendation: put in a request to HQ to have the whole element be made clickable.

– Image too big

– Anchors missed

– Participants did not fully understand this content

– Participants wanted to click on the box

PCD V2

What’s Changed?

Header made smaller and placed on dark background to save space and help dto emphasise it.

More images showing products in context

Anchor links move above key visual for greater consistency

Content re -organised around participants criteria

Progress meter reduced in size, small font and thinner line to help de- emphasise it.

PCD V2 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/Onboarding/onboarding-overview12/

A link to the Virtual Assistant is introduced to the page

Images replace icons to create more engagement and variety

PCD V2

Finding: a smaller hero image helped participants see more of page.

Issue: participants’ first interaction tended to also mark the end of the page exploration. Only one participant scanned the entire page before choosing what to click on.

Recommendation: getting users to explore the entire page is a nice to have, but not necessary for its function. That they find relevant content is.

Issue: separating style, budget, type and colour into individual ‘Choose by’ options made the information clear, but some participants expected behaviour similar to a configurator as these options appeared to be sequential.

Recommendation: change the label ‘Choose by’ to ‘Explore’ or ‘Find Out More’.

Issue: the link to the Virtual Assistant was introduced but also missed and ignored by participants. Those who saw it were unwilling to interact with it as they thought it looked like an advert.

Recommendation: try a different visual treatment that does not look like a promotion.

PCD V2 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/Onboarding/onboarding-overview12/

Anchor menu missed

Anchor links move above key visual for greater consistency

Virtual Assistant ignored

PCD V3

What’s Changed?

Anchors replaced with breadcrumb.

Progress meter reduced in size, small font and thinner line to help de- emphasise it.

Label change to set participants expectation.

Tabs used to make page shorter and help focus participants on content available.

Integrated given its own content.

Virtual assistant given a different visual treatment. Copy swapped to set participants expectations.

Virtual Assistant grouped with see all fridges.

PCD V3 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/Onboarding/onboarding-overview1211/

PCD V3

Finding: combing size, type, colour and feature into a single tabbed component worked as a navigational device.

Finding: combining features shortened the page in order to encourage exploration, but this had no effect on the participants that were shown it.

Finding: the ‘Choose by’ heading replaced with ‘Discover’ to set expectation. This worked to some extent.

Issue: some participants interacted with this, but expected to link through to a filtered PDP from attributes colour, size, and features.

Finding: the Type of Fridge linked behaved as participants expected.

Recommendation: change the order of the tabs, with type first and ensure colour, size and features all link to a pre-filtered PFP.

Issue: the redesigned link to Virtual Assistant (VA) did not attract more attention as participants did not scroll past the first item with which they interacted.

Recommendation: consider moving it above the primary categories.

Finding: changing the VA copy to read ‘Answer three questions’ set participants’ expectation of what they would get from it.

PCD V3 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/Onboarding/onboarding-overview1211/

Breadcrumb ignored.

Progress meter reduced in size, small font and thinner line to help de- emphasise it.

Participants expected to link to PFP.

Participants did not scroll beyond this point

Search Landing Page (SLP) V1

Image too big.

Anchors missed.

Carousel missed.

Copy was not useful.

Finding: page engagement was hindered by lack of relevant copy and imagery.

Issue: as with the PCD, participants did not scroll. The key visual image was too large, discouraging participants from exploring the page.

Recommendation: reduce the height of the key visual in order to pull additional page content into the view port.

Issue: again, the anchor menu under the key visual was mostly ignored.

Recommendation: move above the key visual and consider a more descriptive label, ‘see what’s in the page’.

Issue: the phrase ‘Large Capacity’ was not understood.

Recommendation: provide dimensions and litres. Some participants commented that a capacity helped for comparison as it provided a single metric.

Issue: participants missed the carousel. This was especially problematic on mobile and meant participants were not engaging with features and benefits.

Recommendation: remove the carousel and tile the features and benefits in the page.

SLP V1 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/UX-DA/da-seo-category-af21111111/

Issue: the copy in general was seen as marketing jargon.

Recommendation: provide tangible content that addresses what customers need to know.

Issue: participants did not want to click on the ‘Buy Now’ CTA as they felt that they were not ready to buy.

Recommendation: ‘Buy Now’ is misleading and too pushy for content at this stage of the customer journey. Try ‘learn more’.

Capacity not understood

‘Buy now’ off putting.

Lack of images hinders engagement.

SLP V2

What’s Changed?

Header made smaller and placed on dark background to save space and help de- emphasise it.

Features and benefits broken out into tiles.

Anchor links move above key visual for greater consistency.

Copy from AO.com used.

Icons taken from .com.

‘Learn more’ replaces ‘buy now’.

A link to the Virtual Assistant is introduced to the page.

SLP V2

Finding: providing more relevant copy and imagery helped participants engage with the page.

Finding: breaking the feature benefits out of the carousel got more engagement from participants. Some participants would scan the image, read the headline and only read the description if relevant.

Issue: subheadings were missed.

Recommendation: consider altering the size of the heading and sub-heading to reduce the difference.

Issue: the Anchor menu above key visual was missed by participants.

Recommendation: remove the anchor menu as it provides no benefits.

Issue: participants still not engaging with ‘Related Products’.

Recommendation: some participants commented that Key Features, Related Products and Featured products all looked very similar. Try making these items more visually distinct.

Issue: as with the PCD, the link to the Virtual Assistant was introduced but also missed and ignored by participants. Those who saw it were unwilling to interact with it as they thought it looked like an advert.

Recommendation: try a different visual treatment that does not look like a promotion.

Anchor menu missed

Virtual Assistant ignored

Subheadings missed

Related products missed and or ignored

SLP V3

What’s Changed?

Anchors replaced with breadcrumb.

Capacity explained.

SLP V3 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/UX-DA/da-seo-category-af211/

Virtual assistant given a different visual treatment. Copy swapped to set participants expectations.

Tab feature from PCD introduced to aid navigation.

Featured products dropped to three items.

Virtual Assistant grouped with see all fridges.

SLP V3

Issue: the breadcrumb was not used to aid navigation.

Recommendation: leave the breadcrumb as it is a familiar model.

Finding: the copy from AO.com was well received by participants.

Finding: participants were able to progress their journey to PDP, PFP and the Virtual Assistant.

Issue: there was limited interaction with ‘Discover our entire range’ but participants preferred to return to PCD.

Recommendation: try a different heading and change the order of items.

Finding: some participants were interested in reading about features, but for the most part were primarily interested in reaching a PDP.

SLP V3 https://qaweb.xxxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/UX-DA/da-seo-category-af211/

Limited engagement.

Breadcrumb ignored.

Product Detail Page (PDP) V1

Finding: reviews were important to some users, but not all. There was some scepticism as they are on the manufacturer’s site.

Finding: the most important content was product images and the product specs.

Finding: ‘How it stacks up’ well liked. The ability to compare models was considered a ‘must have’ by most users.

Issue: User Manuals take up significant screen space and are not needed at this point.

Issue: ‘See all fridges’ and ‘Virtual Assistant’ at bottom of page were not seen on mobile as the component scrolls rather than stacks.

Recommendation: swap this out for a different component that stacks.

Reviews important.

Carousel missed.

Copy was not useful.

Specs important, but in this format the content is hard to comprehend.

Content not relevant.

Content liked , participants used it to compare.

Virtual Assistant missed on mobile.

PDP V2

What’s Changed?

Price bar removed.

Copy from .com.

Features and benefits broken out into tiles.

Specs table replaces previous specs layout.

Reviews moved below specs.

Virtual Assistant given a different treatment to avoid scroll on mobile

PDP V2

Issue: the product overview content takes up too much room on this page when shown as strips, and is probably not relevant.

Issue: the overview content forced participants to scroll down to find the product specs.

Finding: participants thought that the overview was repetitive and not necessary at this stage of the journey. However, it is worth keeping in mind that they had navigated to this page seeing similar content on the SLPs.

Recommendation: consider changing the order of content in this page to place specs above.

Issue: participants were frustrated with the product overview points. They were seen as jargon and not relevant.

Recommendation: ensure all content and descriptions are written in plain English.

Issue: the Virtual Assistant link was missed by everybody.

Recommendation: change the way the Virtual Assistant is presented. Ensure that it does not look like a promotion.

Features and benefits take up too much space.

Participants did not like marketing tone of copy.

Virtual Assistant missed by all participants.

PDP V3

What’s Changed?

Breadcrumb inserted above configurator for consistency.

PDP V3 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/UX-DA/da-pdp-01/

Virtual assistant given a different visual treatment. Copy swapped to set participants expectations.

Tab feature from PCD introduced to aid navigation.

Virtual Assistant grouped with ‘see all fridges’.

PDP V3

Finding: participants skipped over the product overview to the specs.

Recommendation: specs and Key Features should be moved beneath the configurator.

Finding: some participants interacted with the Virtual Assistant and Discover tabs components to navigate to new content.

Key features and product spec were of interest to participants.

PDP V3 https://qaweb.xxxxxxx.com/uk/component- testing/UX-DA/da-pdp-01/

Some interaction with Virtual Assistant.

Virtual Assistant

The virtual assistant prototype was developed from a live example on xxxxxxx.com/us.